Top notch

Design journalist Anders Modig made the trek across the pond from Basel to New York for an extended lunch with Charles G. Stone II, CEO of Fisher Marantz Stone.

Vill du fortsätta läsa?

Denna artikel är låst och endast tillgänglig för prenumeranter som skapat konto på ljuskultur.se. Som prenumerant kan du läsa samtliga artiklar från det senaste numret på nätet och får tillgång till ett växande arkiv av tidningens rika material. Är du redan prenumerant klicka på Logga in nedan för att logga in eller skapa konto.

Bli prenumerantAlongside circus, Vegas entertainment and wizardry, lighting design is the only industry whose representatives keep referring to magic. I understand what they mean – light is magic – but should magic really be a sales proposition? Still, I have heard it before; I am used to it. Thus I am not overly surprised when even somebody like Charles Stone, CEO of Fisher Marantz Stone, one of the world’s foremost lighting designers with finished projects in 22 countries, mentions the m-word without shame.

“Our clients come to us to buy some magic – which we sell … very expensive,” Charles whisperingly ends with an endearing smile. “They look at our portfolio and say ‘I want some of that!’ – That’s why they hire us. My privilege is that we have not only 10 projects in our portfolio to show them, not only 100, we have hundreds of fantastic projects in our portfolio to share. And our best project is always the next project. We have so many exciting projects in the pipeline. Sometimes I have to ask myself: how do I manage this extraordinary heritage, how can I expand our vision?”

What he says is, just like him, woven in an unmistakably New York cocoon of experience, humor and class – Charles’s full name is Charles G. Stone II. Thus his bold statements don’t come across as boasting because they are true. They trigger respect. They stir up curiosity. And he does have the portfolio to back it all up: World Trade Center, Burj Khalifa, Canary Wharf, Grand Hyatt Tokyo, Museum of Islamic Arts, Grand Central Terminal, Carnegie Hall, Radio City Music Hall, LVMH Tower, JFK Airport, brands like Chanel, Graff, Gucci, Ikea … I could fill pages with the projects carried out since 1971 when Jules Fisher and Paul Marantz founded the company in a New York basement. Just about every project is top-notch when you look at design quality, cultural significance and level of architecture. No wonder Fisher Marantz Stone has enough awards and diplomas to cover a Chinese square.

“An award is always the result of a collaboration with the architecture and the owner. Through true collaboration we can accomplish results that we couldn’t reach on our own,” says Charles.

For a European to hear Charles wax lyrical becomes New York in a nutshell, because it simply is – and it is big. I am also smitten by his self-assuredness that makes it a nonquestion for him to choose a ruby red Campari soda, which he will sip slowly as if it were the perfect accompaniment to the roasted tomato soup and the carbonara.

With my own seafood pasta I am more traditional in choice of drink. As we toast in the near-empty, now sadly defunct Italian haunt across the road from the office’s back door, I say a silent prayer to the house white not to go all roller coaster on my jetlagged being. During our initial small talk we send out a few hooks regarding mutual friends and colleagues in architecture and lighting, a game where Charles of course has the upper hand since FMS has worked with everybody over the years.

A friendly waiter in a red waistcoat passes by and completes our plates with a few creaking grinds of the pepper mill as a biting wind taps icy drops on the vaulted windows. “I think we have the perfect food for one of these cold May days,” says Charles, looking up.

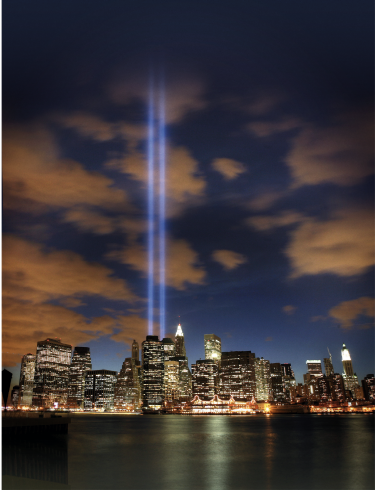

It is hard to go to New York and not see works made by FMS. If you are here around 9/11, it is even impossible, since they produce the annual remembrance lights that shine into the sky: the Tribute in Light.

“It takes a few days to set it up perfectly. You can’t just take 88 pieces of 7,000 watt xenon lights and point them straight on an afternoon. The hardest thing is to make them absolutely vertical – it is like getting a bunch of kindergarten kids to walk in a line. To know what is truly straight up we work really traditionally, with a Roman plumb bob, and we also have a team of people with walkie-talkies in different locations giving reports,” says Charles, while stroking the bristles on his chin, equally as long as the thinning strands on his pate.

FMS also lit the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, where they equipped the waterfall with water-cooled LED tubes custom-made in collaboration with the supplier. The latest addition to the spot whose events changed the worldview is the World Trade Center Transportation Hub designed by Santiago Calatrava. This is capped by the Oculus, an organic shape reminiscent of whalebones or giant eyelashes, or in Calatrava’s own words, “A bird released from a child’s hands.” The sculptural construction opened to the public in March 2016 is extremely light, since the whole interior is painted in a dazzling white.

The 100-yard-long Oculus, a self-supporting structure completely devoid of pillars, is an extreme exercise in daylighting with ceiling windows across the entire edifice, thus unadulterated daylight trickles down to the subterranean train platforms through openings in the multi-story mezzanine.

Of course the natural light is supplemented with electrical light, mainly in the form of indirect lights hidden in the quills. Most renderings and photos show the exterior as a stark white peace dove, but often they are filled by a subtle leopard print pattern created by reflections from the surrounding skyscrapers, forever changing with the moving sun.

When it comes to classical environments, the recently renovated Armory on Park Avenue is one of New York’s most talked about of late. Here FMS worked with the Basel architect, Herzog and de Meuron. Unbeknownst to many, this also has a connection to 9/11, since the stately building served as an emergency hospital after the attack; the first time Herzog and de Meuron arrived there were still wires hanging everywhere in an archaeological reminiscence of this usage. Together the two companies have taken the building back to its heyday. Every room is unique in size and expression, and here the main scheme of the lighting was to dare to preserve contrasts through very clear thin-beam point sources, and to enhance the weight of the building through sparsely lighting elegant ornamental wooden panels. “The weight of the building in enhanced through sparsely lighting elegant ornamental wooden panels.”

All the public prestige buildings aside – right now Charles is very excited about a law office in Washington, DC. The headquarters project for the law firm, Covington won two GE Edison Awards in May 2016 and a Lumen Award in June 2016.

“It is hard to win awards with office interiors – they are so normal,” Charles says about the 500,000 square feet glass building, which is a textbook example of modern, minimalist precision. The architect, Lehman Smith McLeish has simply achieved something refined, understated and professional with a light touch of futurism. FMS did all the interior light, focusing on a uniform illumination. Recessed LED strips frame the rooms and add life to the glass facade, and a great emphasis has been placed on achieving a feeling of uniform light where different environments meet: when you open the door of an office and enter a corridor, from the foyer to the elevator lobby, where you enter or leave the conference room. According to Stone such transitions should be resolved with a less is more strategy.

“If you complicate too much in each of the respective spaces, there will be chaos when they meet,” he says matter-of-factly.

In the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the tallest building in the world, FMS worked with all the spaces in the generous lobby and the Armani Hotel. Working on this true skyscraper whose concept, suitably enough, is based on a desert lily, demanded one virtue above all: patience. It took eight years from models, renderings and conceptual sketches to the project finally being completed, towering 2,722 feet above the ground. Another project in the Middle East is the Museum of Islamic Art, which visitors reach from the corniche that runs along the bay of Doha in Qatar’s capital. The museum, which opened in 2008, is a project of architect, I.M. Pei, who will celebrate his 100th birthday in April 2017. “This museum is etheric, it really pushes boundaries,” Charles says in awe of the architecture. The form of building blocks stapled in an octagon is inspired by the shape of a simple ablution block adjacent to a mosque in Egypt. The light is signified by a giant bay window spanning all four floors. The exhibitions on three floors are placed in peripheral, relatively dark rooms around the central daylit space. This simplicity is beautiful and necessary, since a majority of the artifacts and artworks are extremely sensitive to UV light.

Charles tells me that his focus is taking care of clients and staff. He makes sure clients get what they want, and ensures that the technology is interacting with the design, and the design is correlating with the clients’ aspirations. A helpful tool is the four-step model mockup-documentation-implementation-evaluation. But perhaps even more important is setting time aside for the simple and important things in life – to meet, to talk with the clients, to make sure that they are happy and satisfied with the work. In his strategy there are no figures for happiness.

But I guess that happiness in lighting design is now spelled LED?

“Yes, we are living in an LED world. I call it the LED tsunami, and it is here whether you want it or not. All the new research goes into LED; all the new luminaires are LED. Everything else is simply left behind. Since 2014 – if you judge from what is presented at Light + Building in Frankfurt – LED is now available in all applications, from streetlights, luminaires for industrial environments and stadiums down to boutiques, shelves, wardrobes and everything in between. Digital LED is now covering the whole spectrum, and we take it for granted. But you just have to go back four or five years to realize what an extraordinary development LED has gone through in an incredibly short time. Now everything is available in LED, and unlike before, everything is available in good quality, which is a nice evolution of late.”

What is the most important step in this evolution?

“Now you have excellent color rendering, for instance with GaN-on-GaN technology, with SORAA being one of the manufacturers. Their manufacturing technology also eliminates a few steps; thus it is more efficient. Supposedly this will make them cheaper when the volumes are big enough; everything is very expensive before you reach a critical mass. Unfortunately we have a Wild West situation at the moment; there are so many manufacturers around. Because of this you have a plethora of systems, control schemes and module sizes – compatibility can be a serious problem if you are not an expert.”

How do you advise your clients in this Wild West, or even jungle, given that they of course want long-term solutions?

“It is difficult, especially since too many clients believe that LED lights last forever, that they are some sort of holy grail of lighting. Of course, they don’t last forever and of course they are not. As you know, they often need more maintenance than the manufacturers claim. And ever since the world’s first gas streetlights were lit on Pall Mall in London on January 28, 1807, lighting technology has had a foundational shift in technology every twenty years. And whenever something new arrives, we forget that the future is not over. Do you remember compact fluorescents? MR16 Halogens? Soon we will also say, do you remember the funny first generation chips for LED? LED will also become history one day, but I have no idea what will replace it. If I knew, I would be smarter and richer.”

Do you get what you pay for?

“Nowadays it is not that simple. Twenty years ago you had to pay more for quality, for instance for a better optical system or a better luminaire. But now with refraction plastic or built-in lenses at the LED point, the cost is pretty much the same for good and bad luminaires. But it is not only about the quality of the luminaire: bad lighting often comes from using the wrong luminaire for the situation. Having said that, I must add that the awareness of light has on the one side become better. But on the other hand not all clients understand that the technology is undergoing constant development.”

Some talk about softer, more flexible solutions.

“For sure, OLED, quantum dots and what have you. There is a strong focus on new technology, which is exciting, but what is often forgotten is that your eyes don’t change. The relationship between light and glare is deeply encoded in the human brain, and it is not likely to change.”

How has all this changed the role of manufacturers?

“They have a new, stronger role, since they to a certain extent dictate the rules. And sometimes they use this recently increased attention to offer lighting design for free. But then the result is what you would expect.”

Do you have an example of this?

“We did the interior lighting design of a museum, and afterwards we discussed possible strategies for the historical facade. And since we’d already done the interior, we suggested only another 10,000 dollars for this extra assignment. In the end, however, the museum didn’t choose us; they chose somebody else. But the result was not good. So they called us again and said, ‘We don’t like the result, could you please do it after all?’ That’s how I found out that it was a well-known manufacturer who’d done the poor job. Of course, we said yes, and we remained at our generous offer. Afterwards I called this manufacturer that I go back years with; we have done many projects together.

‘You did this job, and just so you know, we have been asked to fix it. Who was your consultant?’ I asked him.

‘We did it ourselves.’

‘You took my job. But I don’t have a problem with that; I believe in free enterprise, I am a capitalist. But I must tell you that we just wanted 10,000. How much did you charge?’

‘We did it for free. One of our interns did it.’

‘Well, the intern didn’t make the client happy. And since we have to redo the work, I guess the work wasn’t that great. But above all, do you realize what you just said to me? That you value our work alongside the work of your interns. So, I guess we are competitors from now on? I welcome you. But the next time you are in my office, you will not get farther than the conference room, there will be no more walking around.’

There was a long silence at the other end of the line.

‘That’s reasonable, isn’t it? You are now my competitor, so of course, I cannot share the secrets from our laboratory.’

“Slowly it dawned upon him what they had done,” says Stone with a laugh just as two perfect espressos land softly on the white tablecloth.

After kissing the Scottish lady who owned the restaurant on both cheeks, we cross 18th Street and enter a slow elevator that brings us up to the office, and if I were to sum up my first impression in one word, it would be playfulness. Both founders and a couple of colleagues are testing new tools against a white wall – and the result seems to be that the free mobile app Optical Light is delivering equal results to Minolta’s light meter that somebody just bought for 2,000 dollars. Across the room there is open-hearted experimentation going on in the 700 square foot experiment studio, which is filled from floor to ceiling with models, mockups and different types of ceilings.

“We have a constant laboratory in the studio. We are playing with the future, trying to predict which suppliers will remain top-notch. You have to test, test and do more tests – it is never enough to only listen to their sales pitch.”

But as you said before – the suppliers are now in the driver’s seat?

“Yes, we are dependent on them. But we often alter and customize their products; we add optical parts that modify the performance. We rarely accept the standard methods for control and dimming – we improve them.” “We like to be on the cutting edge but to stay off the bleeding edge.”

How is it different to be a lighting designer in the United States compared with elsewhere in the world?

“Well, the United States has a strong tradition of litigation, and this affects our work. Take stairs for instance – you have to light them. If the owner or the architect doesn’t want to do that, we write them a letter along the lines of ‘you ought to light them, somebody could fall there and sue you; as lighting designer it is our responsibility to protect you from that.’ If they still don’t want to do it – fine. Then we can show the letter that proves that we have done our work in case of a future court case. Once many years ago we were named in litigation that arose when somebody had fallen on the stairs of a discotheque. But we had put lights along the length of the whole stairs, which we showed to the judge, who said ‘you can go home, this is not your fault.’”

Joe, the CFO who’s been with the company for 27 years, walks by.

“Hey Joe, you are the numbers guy, but what do we do with stairs?”

“You light the hell out of ’em.”

We all laugh, but as Charles keeps talking, I notice that he is getting somewhat itchy, since he is on his way to another meeting. Given that he has at least 100 travel days per year, I realize that he has been extremely generous giving me two and a half hours of his time. I reach for my last questions.

Architects often talk about flexibility for future use.

“Everybody talks about it, but somebody has to pay for it – flexibility always costs money. If you, for instance, design a track lighting system for a restaurant of 1,600 square feet, you will need five pieces of track, each 16 feet long. But for future flexibility you will need eight pieces of track, because what happens if they move the bar or change the placement of the tables? This means that somebody must agree to pay for 60 percent more material. In a museum you think about it. In an academic context too, but schools rarely have the budgets. When it comes to boutiques and hotels, it is not necessary – they will tear it down or rebuild it in five or 10 years anyway. In such places it is the other way around – cut away everything that is not absolutely essential.

What is your view on compatibility between different systems?

“I am impressed with strong engineering solutions with solid Wi-Fi signals on the right frequencies that don’t interfere with police radios and the like. But control has become very complicated, because there are so many different control systems. The question is who will own this spaceship control, which is increasingly voice controlled in a fashion like talking to Siri on your phone.”

Where will it end?

“Probably Apple, Google and Amazon will play an increasingly greater role. Alexa is already working with hubs from Amazon. The question is: how we will communicate with the lights. Will the dimmer still be mounted on the wall or will it be in your computer or in your phone? Lutron has, for example, interesting Wi-Fi pucks that can talk to a neighborhood of fixtures. Actually, the “spaceship” technology is already here. I have Alexa in my home in Seattle. Now I just enter the apartment and say ‘turn on the light,’ ‘living room lights on’ or ‘evening atmosphere.’ Who needs buttons? This is coming fast – the spaceship has landed.”

Fisher Marantz Stone is famous for being a groundbreaking pioneer, and you have several secret high-tech clients in Seattle and California. What is the most advanced project that you are working on at the moment?

“The one that starts tomorrow.”

OK, I understand that you must respect nondisclosure agreements. But what is the next project for you?

“I just got back from Seattle, where I have moved to be in close contact with our new studio, which is a part of our larger New York studio – all our 35 employees, whether they are lighting designers, interior architects, architects or office staff, start out in New York – we call it boot camp.”

Last but not least: What is your view on new technology. Do you want to be the cutting-edge pioneers or do you wait until the teething problems are resolved?

“We like to be on the cutting edge but to stay off the bleeding edge.”